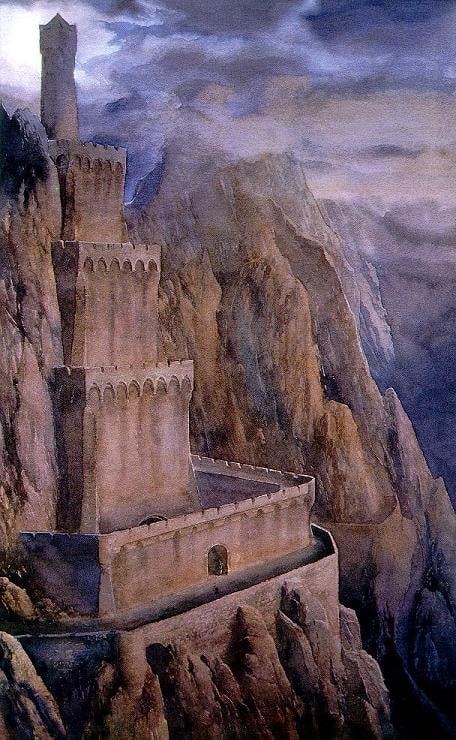

The Grey Havens

There is something that stirs within our hearts that we cannot fully express: a longing and desire that lies beyond the circles of this world. The Sea! The Sea! “Deep in the hearts of all my kindred lies the sea-longing, which it is perilous to stir,” says Legolas, recalling Galadriel’s verse to him:

Legolas Greenleaf long under tree

In joy thou hast lived. Beware of the Sea!

If thou hearest the cry of the gull on the shore,

Thy heart shall then rest in the forest no more.”

The Sea calls us home. Within the encircling waters resounds the echoes of the song of creation. The Sea straddles the circles of this world: beyond it lies our hope unlooked for, our longing unsatiated, our desire most deeply known.

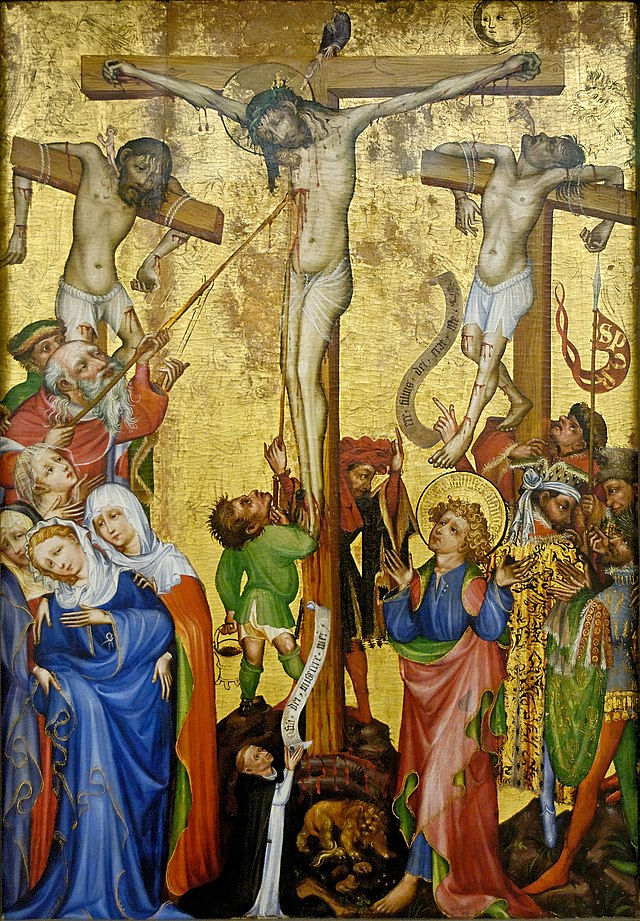

There are some wounds that cannot fully heal: some pains we bear for the remainder of our days. The joys of this world always are tinged with sorrow and grief: for they are passing, they are fading, they are fleeting from our grasp. There is a hard truth to mortal life, to living with virtue and for the sake of good:

But I have been too deeply hurt, Sam. I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so, Sam, when things are in danger: some one has to give them up, lose them, so that others may keep them.”

All of our just and righteous acts of service and courage, mercy and love, may be enough to defend many good and true and beautiful things in this world: but they cannot save ourselves. There are depths in man’s heart and soul that cannot be healed save beyond the circles of this world.

There is tragedy in death: yet therefore there is joy. For death takes beyond – in our passing we travel the straight way across the cosmic Sea – and in doing so lifts the burdens that we mortals carry. As much as there is grief in death, there is also grief in immortality: as Tolkien explains, “The Human-stories of the elves are doubtless full of the Escape from Deathlessness.” We do not know what lies beyond the circles of this world: from even the Valar is the doom of mortal men withheld. Yet from the Grey Havens we can look out across the Sea, swiftly stirring, seagulls in the air, and breathe in the hope of true restoration of our bodies and souls.

The Sea! The Sea! The Sea calls us home: home beyond the circles of this world. Our lives are but mere pilgrimages upon our passing lands, as has our Lenten pilgrimage within the boundaries of Middle-earth. For our ultimate destination lies on white shores, in a far green country under a swift sunrise. Sweet singing voices from that land mingle with the deep music from the beginning of time. We know what we cannot fully express: that we are called to a Good, a Truth, and a Beauty, and until then we are restless, until we can rest in Thee.